Chapter 2: Foundational Concepts

This chapter introduces key concepts in the study of human communication. It begins by summarizing contemporary definitions of communication, highlighting common themes as well as their shortcomings for studying understanding. It then introduces a “message processing” definition of communication, which conceptualizes communication as a process of creating shared mental states between two minds. The balance of the chapter introduces and defines related concepts that will be useful to the study of message processing.

Before diving into past and present scientific models of human communication, it is important to take a step back and spend some time discussing and defining the concepts and ideas used in those models. Just as you might lay out your tools and materials before starting a project (e.g., assembling a piece of furniture, baking a cake, repairing an engine), this chapter aims to lay out foundational concepts in the study of human communication before we get into the details of how it works. Many communication textbooks treat these concepts as primitive terms (i.e., terms that do not need to be defined, because they are widely understood). However—as subsequent discussions of message processing will make clear—this is potentially problematic, as it can lead to ambiguity in what exactly is intended when a term is used. This, in turn, can lead to misunderstandings and/or a lack of precision in theorizing and thinking about important questions.

Communication

Perhaps the most central term of all to the study of message processing is communication. The word “communicate” has its origins in the Latin word “communicare”, which means to “share” or “make common”. (This is the same word root as words like “community” or “common”). Thus, etymologically, when we communicate, what we are doing is making the content of our thoughts common between us. Although we have deliberately defined the term message processing without using the term “communication”, the study of message processing essentially consists of examining how “making our thoughts common” occurs, and what happens during this process.

People have been studying human communication for literally thousands of years. As both (meta)theoretical thinking and research methods have evolved over time, the way people have approached this area has also undergone changes. In the following sections, will look at the ways in which contemporary (i.e., 20th and 21st century) communication scholars have traditionally defined human communication. After considering some of the shortcomings of these definitions for the study of message processing, we propose an alternative definition of communication that better suits those purposes. In addition to this new definition, we will also introduce several other key concepts that will help us study how people create understanding in social interaction.

Traditional Definitions of Communication

Consider the following definitions of communication. All of these come from relatively recent publications focused on communication theory and practice.

“Communication is a social process in which individuals employ symbols to establish and interpret meaning in their social environment” (West & Turner, 2014, p. 5)

Interpersonal communication is a “complex, situated social process in which people who have established a communicative relationship exchange messages in an effort to generate shared meanings and accomplish social goals.” (Burleson, 2010, p. 151)

“[Communication is] any act by which one person gives to or receives from another person information about that person’s needs, desires, perceptions, knowledge, or affective states. Communication may be intentional or unintentional, may involve conventional or unconventional signals, may take linguistic or nonlinguistic forms, and may occur through spoken or other modes” (National Joint Committee for the Communicative Needs of Persons with Severe Disabilities, 1992, p. 2)

“Communication is the relational process of creating and interpreting messages that elicit a response” (Griffin, 2011, p. 6)

“[Communication is] the process through which people use messages to generate meanings within and across contexts, cultures, channels and media” (McCornack, 2010, p. 6).

Although there are some differences in wording, these definitions have a number of elements in common. First and foremost, they all describe communication as involving some form of meaning-making via messages. Second, they all describe communication as a process, or something that is ongoing and unfolds over time through a series of related actions (McCornack, 2010; West & Turner, 2014). Third, all these definitions involve some kind of social or relational component: the process they describe involves people interacting with other people, in a manner that is consequential to that process. In sum, across these definitions, we see agreement that communication is a social process involving messages, and that it results in the generation of meaning.

However, none of these definitions tell or show us how people generate meaning from messages (or, notably, what “meaning” is). They just state that people do. Although most of them acknowledge that communication is a process, which implies a series of actions or events, their focus is on the outcomes or outputs of the process (i.e., meanings, responses, accomplishing social goals). None actually describes what the process involves. In other words, these definitions do not provide much insight into how communication works. (It should be noted that we are not picking on the authors in particular; their definitions are representative of what is found across the discipline, in terms of content.)

These traditional definitions are useful enough for the purposes of scholars interested in outcomes of communication like social and relational influence—which, as noted in Chapter 1, have been the traditional focus of research in the discipline of communication. However, they are not as useful to us, as we are less interested in those outcomes; we are more interested in how the process of communicating works. We need a message-processing definition of communication.

Message Processing Definition of Communication

For our purposes—studying how people create mutual understanding in social interaction—we need a definition of communication that addresses what the process of communication involves, and that explains how people share the content of their minds with others via messages. To meet these needs, we propose the following definition: Communication is the process by which people observe and exhibit social stimuli in order to activate, create, or ascertain meme states in other people, with the goal of creating isomorphic meme states between themselves. We will now look at each part of this definition.

This definition begins by describing communication as a process—that is, something that is ongoing and unfolds over time through a series of related actions (McCornack, 2010; West & Turner, 2014). This is consistent with traditional definitions of communication above. The next part of the definition describes the activities involved in communication: people observe and exhibit social stimuli. Stating that people both observe and exhibit emphasizes that process of communication involves both input (taking in; sensing or perceiving) and output (casting; displaying or presenting) by the parties involved.

Stimuli refers to any kind of sensory input (i.e., something in our environment that is accessible via hearing, sight, touch, taste, smell) that evokes a cognitive, affective, or behavioral reaction. Any environment we are in contains what can be described as a very large amount of energy, in many different forms (e.g., various frequencies of sound, light with various wavelengths). However, we cannot perceive all of it: our senses can only sample from very narrow, non-overlapping bandwidths of that energy. In any given instance, we only attend to some portions of those bandwidths, while other portions of those bandwidths are processed at very low levels of awareness, or not processed at all. Stimuli refers to the portions of those bandwidths that (a) are accessible to our senses and (b) stimulate, or bring about, some kind of response, as opposed to just being present in an environment.

Stimuli can take a wide range of forms: a stimulus (singular of “stimuli”) could be a sound, a gesture, markings on a page, a facial movement or expression, or the act of taking someone’s hand, among many other things. Describing the stimuli that people observe and exhibit as social emphasizes that these stimuli come from and are intended for other people; they are also used for purposes that relate to other people. This is also consistent with traditional definitions of communication, which describe communication as involving a social or relational component.

The following part of the definition describes what these activities (seek to) accomplish: to activate, create, or ascertain meme states in other people. To make sense of this, we must first define what a meme state is. We define a meme as a bounded unit of cultural transmission (Dawkins, 1976). Put another way, a meme is a discrete idea or concept that a person can represent in his or her mind, and can share with others via social interaction.

These definitions direct our attention to several key features of memes. First, as a bounded unit, a meme is discrete: it can be identified as a distinct conceptual entity (i.e., it is a single, specific thing and identifiable as such).

Second, as a unit of transmission, a meme can be passed from one person to another (i.e., shared or replicated), and thus is something that can be communicated. Dawkins (1976)—who coined term “meme”—thought of a meme as comparable to a gene. Genes are replicators whose likelihood of being replicated was directly tied to the value it had for the host. Dawkins thought certain ideas – memes – would be more likely to be replicated or communicated if they proved valuable to the communicators that “host” them.

Third, a meme is a unit of cultural transmission, shared or passed along by social interaction, especially imitation. (The word “meme” actually comes from the Greek word “mimēa”, meaning “that which is imitated”; this word has a common word root with “mimic”.) Essentially, memes are sharable nouns: anything that we can turn into a noun, a discrete thought, and shared with others can be a meme. Happiness, strawberries, Poipu Beach, and doing laundry are all examples of memes. We can think of a meme as a “thing”, in a colloquial sense: if the answer to, “Is that [X] a thing?” is yes, then X has taken on the status of a meme. Indeed, the term “thing” itself has emerged as a meme to reference ideas that have crossed a critical threshold from amorphous concept to something recognized as significant within our cultural consciousness: e.g., “Whisky bacon ice cream? Is that a thing?”

A meme state refers to an organized set of memes that a person represents in their mind at a given point in time. Meme states can vary in their depth and complexity. When people think of a single object (e.g., a dog) or concept (e.g., love), they may be relatively straightforward, consisting of a single primary meme and a few other, associated memes (e.g., feelings of warmth or happiness; memories of a childhood pet, etc.). However, more often, meme states can be considerably more complicated, involving multiple memes and specified relationships between them, as well as the memes associated with those memes and relationships. For example, a mental representation of how our day went, including what we did, where we went, and how we felt about it, is more complex than a representation of just “dog” or “love”.

Activating and creating meme states are the primary objective of someone constructing and “sending” a message: when someone casts or exhibits social stimuli, they are generally doing so with the intention of activating, or bringing about, a particular meme in their fellow communicator’s mind. This notion is grounded in models of human memory (see below), which tell us that we can access memes stored in our memory when we are prompted to by some kind of cue, or stimulus, that is associated with that meme. When we do encounter such a stimulus, the associated meme is brought to conscious attention. This is what is meant by activating a meme. In some cases, we may not already have an “entry” in our memory corresponding to the meme that another communicator is trying to activate. This happens, for example, when people use words we do not know, or tell us about things (people, places, objects) that we are not familiar with. In this case, the stimuli provided may not activate a single, specific meme (or at least, the one intended by our fellow communicator). Instead, they may activate a set of other, potentially related memes that we ultimately use to construct a new meme state; this is the creation of a meme state.

Ascertaining meme states is the primary objective of someone “receiving” or interpreting a message: when someone observes or “receives” social stimuli, they are generally doing so with the intention of figuring out or determining what meme(s) their interlocutor has in mind. When we ask ourselves, “What did s/he mean by saying that?”, we are actually asking “what is the meme state s/he is trying to activate in me?”, or more colloquially, “What does s/he want me to think?”. If the stimuli our interlocutor uses is tightly coupled with the meme state they want to activate, we may have little conscious experience of ascertaining a meme state; rather, the meme state be activated easily and automatically. However, if the stimuli our interlocutor uses are only loosely associated with the meme state they want to activate in our mind, we may experience the process of ascertaining a meme state as conscious and effortful. This issue will be discussed further below (see “Meme Activation Potential”).

The final part of the definition’s content describes the overall aim of communication: with the goal of creating isomorphic meme states between themselves. The word isomorphic means having the same fundamental shape, form and structure. The word is Greek in origin, and has two core components: “iso” means “equal”, while “morph” means “form” or “shape”. Thus, iso-morph-ic describes something having equal, or equivalent, shape to something else. The phrase isomorphic meme states, then, refers to having equivalent, or matching, memes states active across two (or more) people. This is, we argue, what communication ultimately achieves—aligning minds so they are thinking about the same thing.

Indeed, recent research suggests this is precisely what happens when people successfully communicate: they become entrained at a neural level. Entrainment occurs when two systems become highly aligned or synchronized in their behavior (e.g., Hasson Ghazanfar, Galantucci, Garrod, & Keysers, 2012). Recent studies by Dr. Uri Hasson and his colleagues have shown that when people communicate, they become cognitively and neurologically entrained—that is, their brains exhibit highly similar activity (i.e., the same activation in the same regions). This isomorphic meme state, this cognitive and neurological entrainment constitutes understanding.

For our purposes, this definition offers several advantages over traditional definitions of communication. First, as noted just above, it emphasizes the process of communicating, and the creation of understanding, rather than outcomes like influence. Second, and perhaps most importantly, it provides an explanation for how people create understanding, or generate meaning from messages: they perceive stimuli provided by another communicator, and this activates meme states in their mind (i.e., stimuli serve as a cue for memory recall or activation). Finally, this definition’s explanation of how communication works corresponds to the cognitive and neurological processes that have been observed when people communicate. As such, this definition goes beyond providing a loose, metaphorical conceptualization of communication (as many traditional models of communication do) and instead offers something with a physical and physiological basis.

Messages

Another fundamental concept in the study of message processing is, of course, messages. For our purposes, we define messages as any set of stimuli that are designed and organized to activate a particular meme state in another person. A single stimulus—e.g., a sound, a gesture, markings on a page, a facial movement or expression, etc.—can constitute a message in and of itself if it is the only stimulus being used to evoke a particular response. However, more frequently, messages involve multiple stimuli that together have a particular effect. Thus, messages often consist of a number of different stimuli (i.e., more than one individual stimulus) unified by a common cause or goal. For instance, we might try to indicate that we are happy by smiling, saying “This is great”, and using a sincere or genuine tone of voice. All three of these stimuli—facial expression, spoken words, and vocalic tone—together constitute a single message that seeks to evoke the idea of happiness. (Alternatively, we might try to indicate that we are displeased by smiling, saying “This is great”, and using a sarcastic tone of voice. As this example indicates, changing a single element of a message’s “package” can make the message activate a quite different meme state.)

Given the potential of one stimulus to alter the meaning of a message, which stimuli are (and are not) included in a message is an important issue to consider. Depending on the media system (see Chapter 3) communicators may have more or less control over how their message is presented to others, and by extension what stimuli a communicator intends to be included in a message. Some media systems offer fairly clear indications of this: in traditional print books, for example, the line between what is and is not in the book is pretty unambiguous. However, in a majority of communicative contexts, only some of stimuli available to communicators are intended to be part of the message (i.e., intended stimuli), the rest are a part of the surrounding environment, but incidental to the message (i.e., collateral stimuli). For example, we could say “This is great”, intending our words and a sarcastic tone of voice to constitute the message’s stimuli. However, other communicators may not attend to or perceive the message exactly as we, the sender, intended: they might omit something we intended to include (e.g., ignoring the tone of voice and focusing only on words), or include something else (e.g., our facial expression) which the we did not intend. As such, it is important to recognize that the message one communicator exhibits may not exactly match what another communicator observes.

Despite these potential issues, messages have a crucial role in human communication: messages are what people (and other entities) use to activate ideas in other people’s minds. As such, we can think of them as the basic unit of human communication. Often, messages involve formal or established codes in the way that stimuli are used are combined—for instance, a sentence spoken in English uses language, which is a conventional code—but they do not have to.

It should be noted that this text’s definition of “message”, which focuses on perceptible stimuli (i.e., sensory input) contrasts with some other, extant definitions of the term. Rather than using the term to describe to sensory information, some scholars (e.g., Sperber & Wilson, 1986) use the term to refer to the ideas or concepts that stimuli are intended to activate. Defined this way, a message is a mental representation, rather than something observable. This is not the way the term will be used in this text, but this different usage is worth noting, particularly if you are interested in reading other researchers’ work.

The Structure of Memory and Mental Representations

Much has been written on the human brain, its structure, and how this relates to people’s experiences of the world. This topic is largely the domain of cognitive psychology, and a review of current knowledge on this area is outside the scope of this text. However, there are some basic features of the human mind that are foundational to the study of message processing; in what follows, we will briefly summarize those key points.

[For additional information on how memory works, click here for a brief introduction].

First, as you know from your own experience, we store many memes in our minds that we are not necessarily aware of, or attending to, at any given point in time. Every day, we are walking around with a lifetime of memories, a dictionary’s worth of vocabulary, the facts from more than a decade of formal education, and much more, all tucked away in our brains. However, we are not consciously thinking about all of this content all of the time. We can, however, access stored memes or meme states when we are prompted to by some kind of cue, or stimulus, that is associated with the meme state in question. When we do encounter such a stimulus—which, as noted above, can take a wide variety of different forms—the associated meme state is brought to conscious attention. In this text, we refer to this process as the activation of a meme state. Generally, meme states that have been recently activated are easier to activate in the present and (near) future. Some meme states have chronically high resting levels of activation, due to chronic or repeated activation of those (or related) meme states.

According to most widely accepted models of human memory and cognition, the content stored in people’s brains can be visualized as a network. Meme states (e.g., facts, memories) do not exist in isolation; rather, they are connected to one another. Thus, rather than thinking of memories or knowledge as filed in a mental “drawer”, it is more accurate to think of them as nodes (i.e., connection points) in a web.

These connections are created when a meme or meme state is initially learned, or “encoded” into memory, which involves physiological changes in the brain (referred to as memory traces). The number and nature of connections between meme [states] can and does vary. Some meme states have many connections to other meme or meme states, while others have relatively few. For example, you probably have many different meme states (i.e., ideas, concepts, memories) connected to the meme of your home town. In contrast, you probably have relatively few meme states connected to the meme of Capel, a town in Western Australia (unless that happens to be your home town!). Generally, it is easier to access meme states that have more connections, as they have more possible paths leading to them.

The nature of these mental structures have important consequences for message processing. First, the idea that we need external stimuli to activate (i.e., call up, recall) content stored in memory is foundational to recognizing what happens, functionally, when people interact and communicate with each other. Second, the presence of connections (i.e., associations) between memes has consequences for what happens when a meme is activated. Just as moving one node (i.e., connection point) would affect other nodes in a web, activating one meme can potentially affect other meme states that are connected to, or associated with, it.

Meme Activation Potential

As described above, meme activation occurs when a stimulus (e.g., a word, sound, image) results in a particular meme or meme state being accessed in memory and thus brought to our attention. This process sounds fairly straightforward, but can be quite complex in practice. One of the primary reasons for this is that there is not one-to-one correspondence between stimuli and meme states. Rather, the same stimulus can be associated with multiple, different meme states. Homophones (e.g., “two” and “too”) are examples of this in auditory English-language stimuli; homographs (e.g., “pen” as a writing instrument or a fence around farm animals) are examples in written English-language stimuli. Nonverbal behavior is frequently polysemous (i.e., having multiple possible “meanings”, or memes associated with a given stimulus) as well. For example, holding up one’s index and middle finger together could be associated with, and thus activate, (a) “peace”, (b) “two”, or (c) that one is posing for a photograph, among other things.

In social interaction, elements of the context often help us arrive at the meme option that is the most likely, out of all possible options. For example, if a conversation is about school work, we are likely to assume that “pen” refers to a writing instrument rather than a fence. However, if the conversation were about farm animals, the opposite would likely be the case. Similarly, if a restaurant host asks a customer how many people need to be seated and the customer holds up his index and middle finger, this gesture is likely to activate the meme “two”, rather than “peace”, because the customer made the gesture right after the host’s “how many” question.

Often, our minds resolve such potential ambiguities rapidly and automatically. This is particularly the case when there are multiple contextual clues that all consistently support the activation of one particular meme state associated with a stimulus. In these cases, we consider the stimulus or message to have high meme activation potential (MAP). Stimuli with high MAP easily and readily activate a specific meme state in a person’s mind. For example, reading the word “red” likely brings to mind an image of a particular color quite easily. Indeed, sometimes this experience is so rapid and straightforward that we have no conscious experience of determining what a message “meant”; we just experience its meaning.

Stimuli with low MAP, on the other hand, do not readily or easily activate one, specific meme state in someone’s mind. In some cases of low MAP, the stimuli in question may fail to activate anything related to the desired meme. It will activate something, but that something may not be what the creator of a message intended. For example, if you do not know French, hearing or reading the word “pamplemousse” is not likely to bring much that is specific to mind – you have nothing specific associated with that word (stimulus) in your memory. It might bring to mind “French”, and things you associate with “French” (e.g., baguettes, berets). However, these associations will be loosely connected, and you will likely recognize that this is probably not what that stimulus was intended to activate. In other cases of low MAP, stimuli can activate multiple, potentially competing, ideas in a target’s mind. For example, if your friend says, “I’ll see you the beach at 5”, the phrase “the beach” could bring to mind more than one location if a particular beach has not been specified earlier in the conversation.

Generally, stimuli with low MAP lead people to experience feelings of confusion. Confusion is essentially uncertainty about what meme state one communicator thinks that another communicator is seeking to activate with the stimuli provided. In these situations, disambiguation—that is, the process of determining which meme state a communicator intended to bring to mind – can be a conscious and effortful undertaking. If the communicative context allows for interactivity (see above), then communicators may have the opportunity to ask for clarification or help with resolving ambiguities (e.g., asking “Which beach?”). If it is not an interactive context, however, people are left to make the best inference or deduction that they can, and miscommunication is more likely to occur.

It is worth noting that the MAP of a given stimulus or message is not an intrinsic quality of that stimulus or message. Rather, it depends on a number of factors, including the attention, abilities, and cognitive environment (e.g., knowledge, memories) of the target, as well as the nature of the communicative context. The same message will not have the same MAP, or the same effects, for all audiences: a message that might have high MAP to a content area expert (e.g., the terms “between-subjects design”, “latent transition analysis”) can sound like gibberish—and thus have low MAP—to someone unfamiliar with that topic area or its terminology. This highlights an important point we will return to throughout this text: adapting and adjusting both the content and form of messages for different audiences plays a critical role in successfully creating understanding.

Interaction and Interactivity

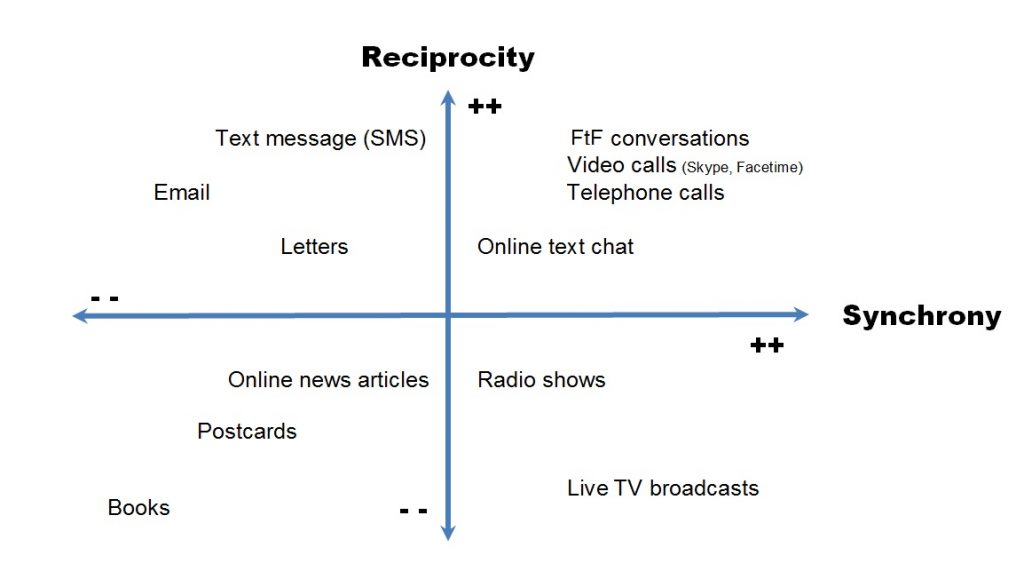

In discussions of communication (and indeed, in the definition message processing we provided in Chapter 1), there are often references to “interaction” or “social interaction”; in describing communicative situations, we often use the term “interactive” or “interactivity”. These are related concepts, and it is important to define them. To interact means “to act in such a way as to have an effect on another”. For communication to occur, some degree of interaction (i.e., instance of interacting) must be possible and present: to make thoughts and ideas common with others, people must be able to act in ways that have effects on others. The successful sharing of ideas between people is, by definition, an effect; if there were no effects, no sharing could take place. However, all communication is not equally interactive. Different situations and communicative contexts involve different levels of interactivity—that is, opportunities for people to engage with, and influence, each other. To better understand how communicative contexts can vary in interactivity, two additional concepts are useful: reciprocity and synchrony.

Reciprocity. Reciprocity is defined as providing exchanges in kind; giving something and receiving something similar back in return. For our purposes, reciprocity is relevant to the flow of stimuli in interaction. In some contexts, stimuli readily flow in two directions; in these situations, communicative reciprocity is high. Face-to-face conversations and telephone conversations are examples of interactive situations with high reciprocity; each person can readily and easily provide and receive social stimuli. In contrast, watching a movie or reading an online article are examples of interactive situations where reciprocity is low. In these situations, stimuli primarily flow in one direction, from the author or creator of the content (e.g., journalist, producer) to the audience members. Although audience members are affected by the content of the show or article, they have very limited opportunities to exert similar (i.e., in kind) effects on the content’s author(s). This constitutes an interactive situation with low reciprocity. Generally, the more a context allows for reciprocal (i.e., bilateral) exchange of stimuli, the more interactive it is considered to be.

Synchrony. Synchrony is defined as occurring at the same time and/or operating following the same time scale. Thus, when two things are aligned in time (i.e., they are simultaneous or closely follow each other in a coordinated way), they are considered synchronous or in sync with each other. Conversely, when two things are separated in time or uncoordinated in their timing, they are considered asynchronous or out of sync with each other. Typically, face-to-face and telephone conversations are examples of synchronous interactive situations; people speak and respond to each other in real time (or with minimal delays) in highly coordinated ways. In contrast, conversations over email can be relatively asynchronous; we can send an email and not get a reply for a day, a week, or even a month (and these delays are not always predictable). Both synchronous and asynchronous communicative contexts can be interactive; communicative contexts that have low levels of synchrony or temporal coordination between communicators can and do still meet the definitional requirements for interactivity. For example, every day people can and do successfully use email to act in ways that affect one another. Similarly, we can be quite affected, cognitively and affectively, by the content of books written by authors decades or even centuries ago. In this sense, long-gone authors are still interacting with readers (audiences) of the stimuli they have produced. Thus, synchrony is not a defining feature of interactivity. However, we discuss it here because the extent to which an exchange is or is not synchronous can have consequences for the form that social interactions take, as well as the way we think about and study interactions.

Both synchrony and reciprocity have important implications for how messages (see below) are constructed and interpreted as people communicate. Specifically, they affect both opportunities to (a) provide feedback on messages, and (b) modify messages once they have been created. In highly reciprocal situations, people can readily and easily provide feedback to each other. This means that communicators have opportunities to seek clarification (e.g., ask for additional detail or elaboration; ask for something to be repeated) if a message is not initially clear to them. In a face-to-face conversation, which is highly reciprocal, we can ask our conversational partner to repeat something we did not hear well (“Sorry, say again?”) or ask for additional information if they use a word, term, or name we are not familiar with (“Who is Dr. Young?”). Because face to face conversations are also highly synchronous, we can get answers to these queries quite quickly, in real time (“I said, ‘pass the salt’”; “She’s a professor in the chemistry department”).

Seeking and providing clarifications are examples of how the formulation of a message, and/or the content of a conversation, can be modified and revised in reciprocal and synchronous contexts. In such situations, the initial version of a message does not have to be the final version. However, when there are few opportunities for reciprocal exchange about message content, a message is unlikely to be changed or revised once it has been constructed. As a result, messaging in highly reciprocal and synchronous contexts tends to be more dynamic, while messaging in minimally reciprocal and asynchronous situations tends to be more static. In situations involving static messaging, communicators’ choices in constructing an initial message are particularly important, because they have limited opportunities to revise or change it later. In situations involving dynamic messaging, message design choices are also important, but there is more inherent flexibility, as communicators can modify messages more easily if needed.

Monologic and Dialogic Approaches to Studying Communication

To date, a majority of research studies looking at human communication have been designed to examine the thoughts and behaviors of one person at a time. If researchers were interested in message construction, they would focus on the thoughts and actions of the message “source” (i.e., creator or originator). If researchers were interested in message effects (including comprehension), they would focus on the thoughts and actions of the message “target” (i.e., audience or recipient). In such studies, the researchers’ unit of analysis—that is, the entity being studied—is the individual. Because it focuses on what a single person is doing or thinking, we call this way of studying communication a monologic approach. (This term shares a common word root with “monologue”, a speech or long talking turn by a single person.) Scholarly work using this approach has certainly contributed to our understanding of message processing. However, it has also been criticized for its minimal focus on interaction.

An alternative way to study communication is a dialogic approach, which examines what happens to two (or more) people together as they interact. (This term shares a common word root with “dialogue”, a conversation between two or more people.) A dialogic perspective directs attention to the ways in which people’s actions and cognitions affect each other as they interact. In this work, the researchers’ unit of analysis is the dyad (or group, in the case of interactions involving more than two people). By studying what happens to both or all individuals engaged in message processing together, researchers can get a more comprehensive picture of how interactants influence each other in the process of creating understanding (Gasiorek & Aune, 2017). Researchers who take a more dialogic perspective contend that successful communication (i.e., that which leads to shared understanding) results in entrainment—that is, convergence or alignment—of interactants’ neurological and psychological states (Garrod & Pickering, 2004), as discussed above. These researchers have argued that the dyad is the smallest unit we can possibly use to effectively study message processing, or the creation of understanding in social interaction (e.g., Hari & Kujala, 2009; Hasson, et al., 2012; Pickering & Garrod, 2004).

Comprehension versus Understanding

As discussed in Chapter 1, the term understanding is often treated as a primitive concept (i.e., as constructs that are so basic or widely recognized that they are not formally defined). This is also the case with comprehension, a term that is often used interchangeably with understanding. In this text, we will treat these as distinct but related constructs. We propose that both involve congruity between (a) the meme states one communicator seeks to activate and (b) the memes actually activated in another communicator’s mind. However, we will use the term comprehension to refer to the outcomes of monologic processes, and understanding to refer to the outcomes of dialogic processes.

More specifically, a person comprehends a message when that message’s stimuli activate the meme states intended by the creator of the message, and that person constructs a corresponding memory representation (Gasiorek & Aune, 2017). Consistent with a monologic approach to studying communication, this definition of comprehension focuses on the processes that occur in a single mind. Here, the individual is the unit of analysis. Generally, discussion of comprehension is best (although not exclusively) suited to the study of static messaging contexts, where there are minimal opportunities for synchronous interactivity, and communicators are removed in time and space from each other.

Alternatively, two people understand each other (or create understanding) when the stimuli they provide each other result in the activation of functionally similar (i.e., isomorphic) meme states in both their minds. Consistent with a dialogic approach to studying communication, this definition of understanding focuses on the mental processes of two (or more) people at a time, and how they correspond to one another. Here, the dyad is the unit of analysis. Generally, discussion of understanding is best suited to the study of dynamic messaging contexts, where there are frequent opportunities for synchronous interactivity, particularly changing and revising message content in response to feedback from fellow communicators.

Implications of a Message Processing Approach

A message processing definition of communication, and the corresponding concepts introduced in this chapter, have some important implications for how we think about communication. First, this definition suggests that the basic objective of the process of communication is to affect memes in other people’s minds. While this is not inconsistent with traditional definitions of communication, it does represent a conceptual shift. Rather than thinking about trying to “transmit” or “convey” a message, which places the emphasis on the message—a unit that is packed up and sent off for someone to “receive”—this definition emphasizes people, and their mental processes. It suggests that if we want to understand how communication works, we need to focus on people, and what is going on in their minds, in a substantive and meaningful way.

Second, by moving away from language and analogies that suggest that meaning is somehow “sent” from one point to another, this definition also allows us to see that meaning is, in fact, created when stimuli (serving as cues) activate memes associated with them. This helps us see how the same message could “mean” different things to different people: the set of stimuli that constitute that message could activate different memes in different minds (depending on what is associated with it; see below).

Third, this definition positions creating understanding—conceptualized as arriving at isomorphic meme states across two or more people—as the primary function of communication. In other words, it claims that this is the first and most fundamental thing that communication accomplishes. Social or relational influence is considered a secondary function, and one that follows from whatever understanding is created. This contrasts with traditional definitions of communication, which implicitly emphasize the outcomes of communication over the creation of understanding.

References

Burleson, B. (2010). The nature of interpersonal communication: A message centered approach. In C. R. Berger, M. E. Roloff and D. R. Roskos-Ewoldsen (Eds.) Handbook of communication science (2nd edition; pp. 145-164). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Dawkins, R. (1976). The Selfish Gene. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Garrod, S., & Pickering, M. J. (2004). Why is conversation so easy? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 8(1), 8–11.

Gasiorek, J., & Aune, K. A. (2017). Text features related to message comprehension. In R. Parrott (Ed.), Oxford Encyclopedia of Health and Risk Message Design and Processing. New York: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.303

Griffin, E. (2011). A first look at communication theory (8th edition). New York: McGraw Hill.

Hari, R., & Kujala, M. V. (2009). Brain basis of human social interaction: From concepts to brain imaging. Physiological Review, 89, 453–479.

Hasson, U., Ghazanfar, A. A., Galantucci, B., Garrod, S., & Keysers, C. (2012). Brain-to-brain coupling: A mechanism for creating and sharing a social world. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 16(2), 114–121.

McCornack, S. (2010). Reflect and relate: An introduction to interpersonal communication (2nd edition). Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s.

National Joint Committee for the Communicative Needs of Persons With Severe Disabilities. (1992). Guidelines for meeting the communication needs of persons with severe disabilities. ASHA, 34 (March, Supp. 7), 1-8.

Pickering, M. J., & Garrod, S. (2004). Toward a mechanistic psychology of dialogue. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 27, 169–226.

Sperber, D., & Wilson, D. (1986). Relevance: Communication and cognition. Oxford: Blackwell.

West, R., & Turner, L. H. (2014). Introducing communication theory: Analysis and application (5th edition). New York: McGraw Hill Education.