Acid-Base Equilibria

Buffers

OpenStaxCollege

[latexpage]

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the composition and function of acid–base buffers

- Calculate the pH of a buffer before and after the addition of added acid or base

A mixture of a weak acid and its conjugate base (or a mixture of a weak base and its conjugate acid) is called a buffer solution, or a buffer. Buffer solutions resist a change in pH when small amounts of a strong acid or a strong base are added ([link]). A solution of acetic acid and sodium acetate (CH3COOH + CH3COONa) is an example of a buffer that consists of a weak acid and its salt. An example of a buffer that consists of a weak base and its salt is a solution of ammonia and ammonium chloride (NH3(aq) + NH4Cl(aq)).

How Buffers Work

A mixture of acetic acid and sodium acetate is acidic because the Ka of acetic acid is greater than the Kb of its conjugate base acetate. It is a buffer because it contains both the weak acid and its salt. Hence, it acts to keep the hydronium ion concentration (and the pH) almost constant by the addition of either a small amount of a strong acid or a strong base. If we add a base such as sodium hydroxide, the hydroxide ions react with the few hydronium ions present. Then more of the acetic acid reacts with water, restoring the hydronium ion concentration almost to its original value:

The pH changes very little. If we add an acid such as hydrochloric acid, most of the hydronium ions from the hydrochloric acid combine with acetate ions, forming acetic acid molecules:

Thus, there is very little increase in the concentration of the hydronium ion, and the pH remains practically unchanged ([link]).

A mixture of ammonia and ammonium chloride is basic because the Kb for ammonia is greater than the Ka for the ammonium ion. It is a buffer because it also contains the salt of the weak base. If we add a base (hydroxide ions), ammonium ions in the buffer react with the hydroxide ions to form ammonia and water and reduce the hydroxide ion concentration almost to its original value:

If we add an acid (hydronium ions), ammonia molecules in the buffer mixture react with the hydronium ions to form ammonium ions and reduce the hydronium ion concentration almost to its original value:

The three parts of the following example illustrate the change in pH that accompanies the addition of base to a buffered solution of a weak acid and to an unbuffered solution of a strong acid.

pH Changes in Buffered and Unbuffered Solutions

Acetate buffers are used in biochemical studies of enzymes and other chemical components of cells to prevent pH changes that might change the biochemical activity of these compounds.

(a) Calculate the pH of an acetate buffer that is a mixture with 0.10 M acetic acid and 0.10 M sodium acetate.

Solution

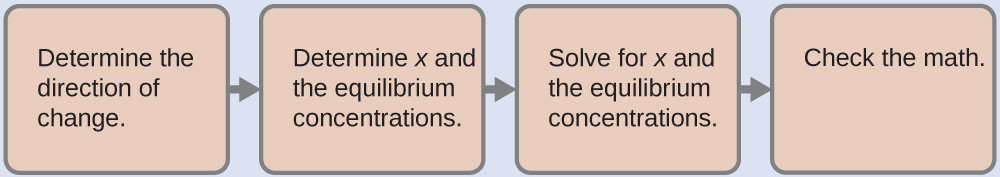

To determine the pH of the buffer solution we use a typical equilibrium calculation (as illustrated in earlier Examples):

- Determine the direction of change. The equilibrium in a mixture of H3O+, \({\text{CH}}_{3}{\text{CO}}_{2}{}^{\text{−}},\) and CH3CO2H is:

\({\text{CH}}_{3}{\text{CO}}_{2}\text{H}\left(aq\right)+{\text{H}}_{2}\text{O}\left(l\right)\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}⇌\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{\text{H}}_{3}{\text{O}}^{\text{+}}\left(aq\right)+{\text{CH}}_{3}{\text{CO}}_{2}{}^{\text{−}}\left(aq\right)\)

The equilibrium constant for CH3CO2H is not given, so we look it up in Appendix H: Ka = 1.8 \(×\) 10−5. With [CH3CO2H] = \(\left[{\text{CH}}_{3}{\text{CO}}_{2}{}^{\text{−}}\right]\) = 0.10 M and [H3O+] = ~0 M, the reaction shifts to the right to form H3O+.

- Determine x and equilibrium concentrations. A table of changes and concentrations follows:

![This table has two main columns and four rows. The first row for the first column does not have a heading and then has the following in the first column: Initial concentration ( M ), Change ( M ), Equilibrium ( M ). The second column has the header of “[ C H subscript 3 C O subscript 2 H ] [ H subscript 2 O ] equilibrium arrow H subscript 3 O superscript plus sign [ C H subscript 3 C O subscript 2 superscript negative sign ].” Under the second column is a subgroup of four columns and three rows. The first column has the following: 0.10, negative x, 0.10 minus sign x. The second column is blank. The third column has the following: approximately 0, x, x. The fourth column has the following: 0.10, x, 0.10 plus sign x.](//pressbooks-dev.oer.hawaii.edu/chemistry/wp-content/uploads/sites/27/2017/09/CNX_Chem_14_06_ICETable16_img.jpg)

- Solve for x and the equilibrium concentrations. We find:

\(x=1.8\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{-5}M\)

and

\(\left[{\text{H}}_{3}{\text{O}}^{\text{+}}\right]\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}=0+x=1.8\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{-5}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}M\)Thus:

\(\text{pH}=\text{−log}\left[{\text{H}}_{3}{\text{O}}^{\text{+}}\right]\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}=\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{−log}\left(1.8\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{-5}\right)\)\(=4.74\) - Check the work. If we calculate all calculated equilibrium concentrations, we find that the equilibrium value of the reaction coefficient, Q = Ka.

(b) Calculate the pH after 1.0 mL of 0.10 M NaOH is added to 100 mL of this buffer, giving a solution with a volume of 101 mL.

First, we calculate the concentrations of an intermediate mixture resulting from the complete reaction between the acid in the buffer and the added base. Then we determine the concentrations of the mixture at the new equilibrium:

![Eight tan rectangles are shown in four columns of two rectangles each that are connected with right pointing arrows. The first rectangle in the upper left is labeled “Volume of N a O H solution.” An arrow points right to a second rectangle labeled “Moles of N a O H added.” A second arrow points right to a third rectangle labeled “Additional moles of N a C H subscript 3 C O subscript 2.” Just beneath the first rectangle in the upper left is a rectangle labeled “Volume of buffer solution.” An arrow points right to another rectangle labeled “Initial moles of C H subscript 3 C O subscript 2 H.” This rectangle points to the same third rectangle, which is labeled “ Additional moles of N a C H subscript 3 C O subscript 2.” An arrow points right to a rectangle labeled “ Unreacted moles of C H subscript 3 C O subscript 2 H.” An arrow points from this rectangle to a rectangle below labeled “[ C H subscript 3 C O subscript 2 H ].” An arrow extends below the “Additional moles of N a C H subscript 3 C O subscript 2” rectangle to a rectangle labeled “[ C H subscript 3 C O subscript 2 ].” This rectangle points right to the rectangle labeled “[ C H subscript 3 C O subscript 2 H ].”](http://pressbooks-dev.oer.hawaii.edu/chemistry/wp-content/uploads/sites/27/2017/09/CNX_Chem_14_06_steps2_img.jpg)

- Determine the moles of NaOH. One milliliter (0.0010 L) of 0.10 M NaOH contains:

\(0.0010\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\overline{)\text{L}}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\left(\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\frac{0.10\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{mol NaOH}}{1\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\overline{)\text{L}}}\right)\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}=1.0\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{-4}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{mol NaOH}\)

- Determine the moles of CH2CO2H. Before reaction, 0.100 L of the buffer solution contains:

\(0.100\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\overline{)\text{L}}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\left(\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\frac{0.100\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{mol}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{\text{CH}}_{3}{\text{CO}}_{2}\text{H}}{1\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\overline{)\text{L}}}\right)\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}=1.00\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{-2}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{mol}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{\text{CH}}_{3}{\text{CO}}_{2}\text{H}\)

- Solve for the amount of NaCH3CO2 produced. The 1.0 \(×\) 10−4 mol of NaOH neutralizes 1.0 \(×\) 10−4 mol of CH3CO2H, leaving:

\(\left(1.0\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{-2}\right)\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}-\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\left(0.01\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{-2}\right)\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}=0.99\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{-2}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{mol}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{\text{CH}}_{3}{\text{CO}}_{2}\text{H}\)

and producing 1.0 \(×\) 10−4 mol of NaCH3CO2. This makes a total of:

\(\left(1.0\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{-2}\right)+\left(0.01\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{-2}\right)\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}=1.01\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{-2}\text{mol}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{\text{NaCH}}_{3}{\text{CO}}_{2}\) - Find the molarity of the products. After reaction, CH3CO2H and NaCH3CO2 are contained in 101 mL of the intermediate solution, so:

\(\left[{\text{CH}}_{3}{\text{CO}}_{2}\text{H}\right]\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}=\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\frac{9.9\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{-3}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{mol}}{0.101\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{L}}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}=0.098\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}M\)\(\left[{\text{NaCH}}_{3}{\text{CO}}_{2}\right]\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}=\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\frac{1.01\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{-2}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{mol}}{0.101\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{L}}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}=0.100\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}M\)

Now we calculate the pH after the intermediate solution, which is 0.098 M in CH3CO2H and 0.100 M in NaCH3CO2, comes to equilibrium. The calculation is very similar to that in part (a) of this example:

This series of calculations gives a pH = 4.75. Thus the addition of the base barely changes the pH of the solution ([link]).

(c) For comparison, calculate the pH after 1.0 mL of 0.10 M NaOH is added to 100 mL of a solution of an unbuffered solution with a pH of 4.74 (a 1.8 \(×\) 10−5–M solution of HCl). The volume of the final solution is 101 mL.

Solution

This 1.8 \(×\) 10−5–M solution of HCl has the same hydronium ion concentration as the 0.10-M solution of acetic acid-sodium acetate buffer described in part (a) of this example. The solution contains:

As shown in part (b), 1 mL of 0.10 M NaOH contains 1.0 \(×\) 10−4 mol of NaOH. When the NaOH and HCl solutions are mixed, the HCl is the limiting reagent in the reaction. All of the HCl reacts, and the amount of NaOH that remains is:

The concentration of NaOH is:

The pOH of this solution is:

The pH is:

The pH changes from 4.74 to 10.99 in this unbuffered solution. This compares to the change of 4.74 to 4.75 that occurred when the same amount of NaOH was added to the buffered solution described in part (b).

Check Your Learning

Show that adding 1.0 mL of 0.10 M HCl changes the pH of 100 mL of a 1.8 \(×\) 10−5M HCl solution from 4.74 to 3.00.

Initial pH of 1.8 \(×\) 10−5M HCl; pH = −log[H3O+] = −log[1.8 \(×\) 10−5] = 4.74

Moles of H3O+ in 100 mL 1.8 \(×\) 10−5M HCl; 1.8 \(×\) 10−5 moles/L \(×\) 0.100 L = 1.8 \(×\) 10−6

Moles of H3O+ added by addition of 1.0 mL of 0.10 M HCl: 0.10 moles/L \(×\) 0.0010 L = 1.0 \(×\) 10−4 moles; final pH after addition of 1.0 mL of 0.10 M HCl:

If we add an acid or a base to a buffer that is a mixture of a weak base and its salt, the calculations of the changes in pH are analogous to those for a buffer mixture of a weak acid and its salt.

Buffer Capacity

Buffer solutions do not have an unlimited capacity to keep the pH relatively constant ([link]). If we add so much base to a buffer that the weak acid is exhausted, no more buffering action toward the base is possible. On the other hand, if we add an excess of acid, the weak base would be exhausted, and no more buffering action toward any additional acid would be possible. In fact, we do not even need to exhaust all of the acid or base in a buffer to overwhelm it; its buffering action will diminish rapidly as a given component nears depletion.

The buffer capacity is the amount of acid or base that can be added to a given volume of a buffer solution before the pH changes significantly, usually by one unit. Buffer capacity depends on the amounts of the weak acid and its conjugate base that are in a buffer mixture. For example, 1 L of a solution that is 1.0 M in acetic acid and 1.0 M in sodium acetate has a greater buffer capacity than 1 L of a solution that is 0.10 M in acetic acid and 0.10 M in sodium acetate even though both solutions have the same pH. The first solution has more buffer capacity because it contains more acetic acid and acetate ion.

Selection of Suitable Buffer Mixtures

There are two useful rules of thumb for selecting buffer mixtures:

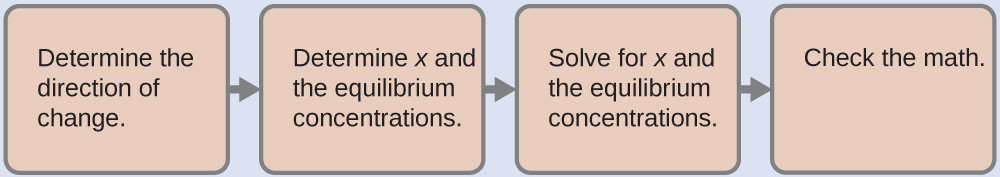

- A good buffer mixture should have about equal concentrations of both of its components. A buffer solution has generally lost its usefulness when one component of the buffer pair is less than about 10% of the other. [link] shows an acetic acid-acetate ion buffer as base is added. The initial pH is 4.74. A change of 1 pH unit occurs when the acetic acid concentration is reduced to 11% of the acetate ion concentration.

The graph, an illustration of buffering action, shows change of pH as an increasing amount of a 0.10-M NaOH solution is added to 100 mL of a buffer solution in which, initially, [CH3CO2H] = 0.10 M and \(\left[{\text{CH}}_{3}{\text{CO}}_{2}{}^{\text{−}}\right]\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}=0.10\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}M.\)

![A graph is shown with a horizontal axis labeled “Added m L of 0.10 M N a O H” which has markings and vertical gridlines every 10 units from 0 to 110. The vertical axis is labeled “p H” and is marked every 1 unit beginning at 0 extending to 11. A break is shown in the vertical axis between 0 and 4. A red curve is drawn on the graph which increases gradually from the point (0, 4.8) up to about (100, 7) after which the graph has a vertical section up to about (100, 11). The curve is labeled [ C H subscript 3 C O subscript 2 H ] is 11 percent of [ C H subscript 3 CO subscript 2 superscript negative].](//pressbooks-dev.oer.hawaii.edu/chemistry/wp-content/uploads/sites/27/2017/09/CNX_Chem_14_06_buffer.jpg)

- Weak acids and their salts are better as buffers for pHs less than 7; weak bases and their salts are better as buffers for pHs greater than 7.

Blood is an important example of a buffered solution, with the principal acid and ion responsible for the buffering action being carbonic acid, H2CO3, and the bicarbonate ion, \({\text{HCO}}_{3}{}^{\text{−}}.\) When an excess of hydrogen ion enters the blood stream, it is removed primarily by the reaction:

When an excess of the hydroxide ion is present, it is removed by the reaction:

The pH of human blood thus remains very near 7.35, that is, slightly basic. Variations are usually less than 0.1 of a pH unit. A change of 0.4 of a pH unit is likely to be fatal.

The Henderson-Hasselbalch Equation

The ionization-constant expression for a solution of a weak acid can be written as:

Rearranging to solve for [H3O+], we get:

Taking the negative logarithm of both sides of this equation, we arrive at:

which can be written as

where pKa is the negative of the common logarithm of the ionization constant of the weak acid (pKa = −log Ka). This equation relates the pH, the ionization constant of a weak acid, and the concentrations of the weak acid and its salt in a buffered solution. Scientists often use this expression, called the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation, to calculate the pH of buffer solutions. It is important to note that the “x is small” assumption must be valid to use this equation.

Lawrence Joseph Henderson (1878–1942) was an American physician, biochemist and physiologist, to name only a few of his many pursuits. He obtained a medical degree from Harvard and then spent 2 years studying in Strasbourg, then a part of Germany, before returning to take a lecturer position at Harvard. He eventually became a professor at Harvard and worked there his entire life. He discovered that the acid-base balance in human blood is regulated by a buffer system formed by the dissolved carbon dioxide in blood. He wrote an equation in 1908 to describe the carbonic acid-carbonate buffer system in blood. Henderson was broadly knowledgeable; in addition to his important research on the physiology of blood, he also wrote on the adaptations of organisms and their fit with their environments, on sociology and on university education. He also founded the Fatigue Laboratory, at the Harvard Business School, which examined human physiology with specific focus on work in industry, exercise, and nutrition.

In 1916, Karl Albert Hasselbalch (1874–1962), a Danish physician and chemist, shared authorship in a paper with Christian Bohr in 1904 that described the Bohr effect, which showed that the ability of hemoglobin in the blood to bind with oxygen was inversely related to the acidity of the blood and the concentration of carbon dioxide. The pH scale was introduced in 1909 by another Dane, Sørensen, and in 1912, Hasselbalch published measurements of the pH of blood. In 1916, Hasselbalch expressed Henderson’s equation in logarithmic terms, consistent with the logarithmic scale of pH, and thus the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation was born.

The normal pH of human blood is about 7.4. The carbonate buffer system in the blood uses the following equilibrium reaction:

The concentration of carbonic acid, H2CO3 is approximately 0.0012 M, and the concentration of the hydrogen carbonate ion, \({\text{HCO}}_{3}{}^{\text{−}},\) is around 0.024 M. Using the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation and the pKa of carbonic acid at body temperature, we can calculate the pH of blood:

The fact that the H2CO3 concentration is significantly lower than that of the \({\text{HCO}}_{3}{}^{\text{−}}\) ion may seem unusual, but this imbalance is due to the fact that most of the by-products of our metabolism that enter our bloodstream are acidic. Therefore, there must be a larger proportion of base than acid, so that the capacity of the buffer will not be exceeded.

Lactic acid is produced in our muscles when we exercise. As the lactic acid enters the bloodstream, it is neutralized by the \({\text{HCO}}_{3}{}^{\text{−}}\) ion, producing H2CO3. An enzyme then accelerates the breakdown of the excess carbonic acid to carbon dioxide and water, which can be eliminated by breathing. In fact, in addition to the regulating effects of the carbonate buffering system on the pH of blood, the body uses breathing to regulate blood pH. If the pH of the blood decreases too far, an increase in breathing removes CO2 from the blood through the lungs driving the equilibrium reaction such that [H3O+] is lowered. If the blood is too alkaline, a lower breath rate increases CO2 concentration in the blood, driving the equilibrium reaction the other way, increasing [H+] and restoring an appropriate pH.

View information on the buffer system encountered in natural waters.

Key Concepts and Summary

A solution containing a mixture of an acid and its conjugate base, or of a base and its conjugate acid, is called a buffer solution. Unlike in the case of an acid, base, or salt solution, the hydronium ion concentration of a buffer solution does not change greatly when a small amount of acid or base is added to the buffer solution. The base (or acid) in the buffer reacts with the added acid (or base).

Key Equations

- pKa = −log Ka

- pKb = −log Kb

- \(\text{pH}=\text{p}{K}_{\text{a}}+\text{log}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\frac{\left[{\text{A}}^{\text{−}}\right]}{\left[\text{HA}\right]}\)

Explain why a buffer can be prepared from a mixture of NH4Cl and NaOH but not from NH3 and NaOH.

Explain why the pH does not change significantly when a small amount of an acid or a base is added to a solution that contains equal amounts of the acid H3PO4 and a salt of its conjugate base NaH2PO4.

Excess H3O+ is removed primarily by the reaction:

\({\text{H}}_{3}{\text{O}}^{\text{+}}\left(aq\right)+{\text{H}}_{2}{\text{PO}}_{4}{}^{\text{−}}\left(aq\right)\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}⟶\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{\text{H}}_{3}{\text{PO}}_{4}\left(aq\right)+{\text{H}}_{2}\text{O}\left(l\right)\)

Excess base is removed by the reaction:

\({\text{OH}}^{\text{−}}\left(aq\right)+{\text{H}}_{3}{\text{PO}}_{4}\left(aq\right)\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}⟶\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{\text{H}}_{2}{\text{PO}}_{4}{}^{\text{−}}\left(aq\right)+{\text{H}}_{2}\text{O}\left(l\right)\)

Explain why the pH does not change significantly when a small amount of an acid or a base is added to a solution that contains equal amounts of the base NH3 and a salt of its conjugate acid NH4Cl.

What is [H3O+] in a solution of 0.25 M CH3CO2H and 0.030 M NaCH3CO2?

\({\text{CH}}_{3}{\text{CO}}_{2}\text{H}\left(aq\right)+{\text{H}}_{2}\text{O}\left(l\right)\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}⇌\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{\text{H}}_{3}{\text{O}}^{\text{+}}\left(aq\right)+{\text{CH}}_{3}{\text{CO}}_{2}{}^{\text{−}}\left(aq\right)\phantom{\rule{5em}{0ex}}{K}_{\text{a}}=1.8\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{-5}\)

[H3O+] = 1.5 \(×\) 10−4M

What is [H3O+] in a solution of 0.075 M HNO2 and 0.030 M NaNO2?

\({\text{HNO}}_{2}\left(aq\right)+{\text{H}}_{2}\text{O}\left(l\right)\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}⇌\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{\text{H}}_{3}{\text{O}}^{\text{+}}\left(aq\right)+{\text{NO}}_{2}{}^{\text{−}}\left(aq\right)\phantom{\rule{5em}{0ex}}{K}_{\text{a}}=4.5\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{-5}\)

What is [OH−] in a solution of 0.125 M CH3NH2 and 0.130 M CH3NH3Cl?

\({\text{CH}}_{3}{\text{NH}}_{2}\left(aq\right)+{\text{H}}_{2}\text{O}\left(l\right)\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}⇌\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{\text{CH}}_{3}{\text{NH}}_{3}{}^{\text{+}}\left(aq\right)+{\text{OH}}^{\text{−}}\left(aq\right)\phantom{\rule{5em}{0ex}}{K}_{\text{b}}=4.4\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{-4}\)

[OH−] = 4.2 \(×\) 10−4M

What is [OH−] in a solution of 1.25 M NH3 and 0.78 M NH4NO3?

\({\text{NH}}_{3}\left(aq\right)+{\text{H}}_{2}\text{O}\left(l\right)\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}⇌\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{\text{NH}}_{4}{}^{\text{+}}\left(aq\right)+{\text{OH}}^{\text{−}}\left(aq\right)\phantom{\rule{5em}{0ex}}{K}_{\text{b}}=1.8\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{-5}\)

What concentration of NH4NO3 is required to make [OH−] = 1.0 \(×\) 10−5 in a 0.200-M solution of NH3?

[NH4NO3] = 0.36 M

What concentration of NaF is required to make [H3O+] = 2.3 \(×\) 10−4 in a 0.300-M solution of HF?

What is the effect on the concentration of acetic acid, hydronium ion, and acetate ion when the following are added to an acidic buffer solution of equal concentrations of acetic acid and sodium acetate:

(a) HCl

(b) KCH3CO2

(c) NaCl

(d) KOH

(e) CH3CO2H

(a) The added HCl will increase the concentration of H3O+ slightly, which will react with \({\text{CH}}_{3}{\text{CO}}_{2}{}^{\text{−}}\) and produce CH3CO2H in the process. Thus, \(\left[{\text{CH}}_{3}{\text{CO}}_{2}{}^{\text{−}}\right]\) decreases and [CH3CO2H] increases.

(b) The added KCH3CO2 will increase the concentration of \(\left[{\text{CH}}_{3}{\text{CO}}_{2}{}^{\text{−}}\right]\) which will react with H3O+ and produce CH3CO2 H in the process. Thus, [H3O+] decreases slightly and [CH3CO2H] increases.

(c) The added NaCl will have no effect on the concentration of the ions.

(d) The added KOH will produce OH− ions, which will react with the H3O+, thus reducing [H3O+]. Some additional CH3CO2H will dissociate, producing \(\left[{\text{CH}}_{3}{\text{CO}}_{2}{}^{\text{−}}\right]\) ions in the process. Thus, [CH3CO2H] decreases slightly and \(\left[{\text{CH}}_{3}{\text{CO}}_{2}{}^{\text{−}}\right]\) increases.

(e) The added CH3CO2H will increase its concentration, causing more of it to dissociate and producing more \(\left[{\text{CH}}_{3}{\text{CO}}_{2}{}^{\text{−}}\right]\) and H3O+ in the process. Thus, [H3O+] increases slightly and \(\left[{\text{CH}}_{3}{\text{CO}}_{2}{}^{\text{−}}\right]\) increases.

What is the effect on the concentration of ammonia, hydroxide ion, and ammonium ion when the following are added to a basic buffer solution of equal concentrations of ammonia and ammonium nitrate:

(a) KI

(b) NH3

(c) HI

(d) NaOH

(e) NH4Cl

What will be the pH of a buffer solution prepared from 0.20 mol NH3, 0.40 mol NH4NO3, and just enough water to give 1.00 L of solution?

pH = 8.95

Calculate the pH of a buffer solution prepared from 0.155 mol of phosphoric acid, 0.250 mole of KH2PO4, and enough water to make 0.500 L of solution.

How much solid NaCH3CO2•3H2O must be added to 0.300 L of a 0.50-M acetic acid solution to give a buffer with a pH of 5.00? (Hint: Assume a negligible change in volume as the solid is added.)

37 g (0.27 mol)

What mass of NH4Cl must be added to 0.750 L of a 0.100-M solution of NH3 to give a buffer solution with a pH of 9.26? (Hint: Assume a negligible change in volume as the solid is added.)

A buffer solution is prepared from equal volumes of 0.200 M acetic acid and 0.600 M sodium acetate. Use 1.80 \(×\) 10−5 as Ka for acetic acid.

(a) What is the pH of the solution?

(b) Is the solution acidic or basic?

(c) What is the pH of a solution that results when 3.00 mL of 0.034 M HCl is added to 0.200 L of the original buffer?

(a) pH = 5.222;

(b) The solution is acidic.

(c) pH = 5.221

A 5.36–g sample of NH4Cl was added to 25.0 mL of 1.00 M NaOH and the resulting solution

diluted to 0.100 L.

(a) What is the pH of this buffer solution?

(b) Is the solution acidic or basic?

(c) What is the pH of a solution that results when 3.00 mL of 0.034 M HCl is added to the solution?

Which acid in [link] is most appropriate for preparation of a buffer solution with a pH of 3.1? Explain your choice.

To prepare the best buffer for a weak acid HA and its salt, the ratio \(\frac{\left[{\text{H}}_{3}{\text{O}}^{\text{+}}\right]}{{K}_{\text{a}}}\) should be as close to 1 as possible for effective buffer action. The [H3O+] concentration in a buffer of pH 3.1 is [H3O+] = 10−3.1 = 7.94 \(×\) 10−4M

We can now solve for Ka of the best acid as follows:

\(\begin{array}{}\\ \\ \\ \\ \phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\frac{\left[{\text{H}}_{3}{\text{O}}^{\text{+}}\right]}{{K}_{\text{a}}}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}=1\\ {K}_{\text{a}}=\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\frac{\left[{\text{H}}_{3}{\text{O}}^{\text{+}}\right]}{1}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}=7.94\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{-4}\end{array}\)

In [link], the acid with the closest Ka to 7.94 \(×\) 10−4 is HF, with a Ka of 7.2 \(×\) 10−4.

Which acid in [link] is most appropriate for preparation of a buffer solution with a pH of 3.7? Explain your choice.

Which base in [link] is most appropriate for preparation of a buffer solution with a pH of 10.65? Explain your choice.

For buffers with pHs > 7, you should use a weak base and its salt. The most effective buffer will have a ratio \(\frac{\left[{\text{OH}}^{\text{−}}\right]}{{K}_{\text{b}}}\) that is as close to 1 as possible. The pOH of the buffer is 14.00 − 10.65 = 3.35. Therefore, [OH−] is [OH−] = 10−pOH = 10−3.35 = 4.467 \(×\) 10−4M.

We can now solve for Kb of the best base as follows:

\(\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\frac{\left[{\text{OH}}^{\text{−}}\right]}{{K}_{\text{b}}}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}=1\)

Kb = [OH−] = 4.47 \(×\) 10−4

In [link], the base with the closest Kb to 4.47 \(×\) 10−4 is CH3NH2, with a Kb = 4.4 \(×\) 10−4.

Which base in [link] is most appropriate for preparation of a buffer solution with a pH of 9.20? Explain your choice.

Saccharin, C7H4NSO3H, is a weak acid (Ka = 2.1 \(×\) 10−2). If 0.250 L of diet cola with a buffered pH of 5.48 was prepared from 2.00 \(×\) 10−3 g of sodium saccharide, Na(C7H4NSO3), what are the final concentrations of saccharine and sodium saccharide in the solution?

The molar mass of sodium saccharide is 205.169 g/mol. Using the abbreviations HA for saccharin and NaA for sodium saccharide the number of moles of NaA in the solution is:

9.75 \(×\) 10−6 mol

The pKa for [HA] is 1.68, so [HA] = \(6.2×{19}^{–9}\) M. Thus, [A–] (saccharin ions) is \(3.90×{10}^{–5}\) M.

Thus, [A−](saccarin ions) is 3.90 \(×\) 10−5M

What is the pH of 1.000 L of a solution of 100.0 g of glutamic acid (C5H9NO4, a diprotic acid; K1 = 8.5 \(×\) 10−5, K2 = 3.39 \(×\) 10−10) to which has been added 20.0 g of NaOH during the preparation of monosodium glutamate, the flavoring agent? What is the pH when exactly 1 mol of NaOH per mole of acid has been added?

Glossary

- buffer capacity

- amount of an acid or base that can be added to a volume of a buffer solution before its pH changes significantly (usually by one pH unit)

- buffer

- mixture of a weak acid or a weak base and the salt of its conjugate; the pH of a buffer resists change when small amounts of acid or base are added

- Henderson-Hasselbalch equation

- equation used to calculate the pH of buffer solutions

![This table has two main columns and four rows. The first row for the first column does not have a heading and then has the following in the first column: Initial concentration ( M ), Change ( M ), Equilibrium ( M ). The second column has the header of “[ C H subscript 3 C O subscript 2 H ] [ H subscript 2 O ] equilibrium arrow H subscript 3 O superscript plus sign [ C H subscript 3 C O subscript 2 superscript negative sign ].” Under the second column is a subgroup of four columns and three rows. The first column has the following: 0.10, negative x, 0.10 minus sign x. The second column is blank. The third column has the following: approximately 0, x, x. The fourth column has the following: 0.10, x, 0.10 plus sign x.](http://pressbooks-dev.oer.hawaii.edu/chemistry/wp-content/uploads/sites/27/2017/09/CNX_Chem_14_06_ICETable16_img.jpg)

![A graph is shown with a horizontal axis labeled “Added m L of 0.10 M N a O H” which has markings and vertical gridlines every 10 units from 0 to 110. The vertical axis is labeled “p H” and is marked every 1 unit beginning at 0 extending to 11. A break is shown in the vertical axis between 0 and 4. A red curve is drawn on the graph which increases gradually from the point (0, 4.8) up to about (100, 7) after which the graph has a vertical section up to about (100, 11). The curve is labeled [ C H subscript 3 C O subscript 2 H ] is 11 percent of [ C H subscript 3 CO subscript 2 superscript negative].](http://pressbooks-dev.oer.hawaii.edu/chemistry/wp-content/uploads/sites/27/2017/09/CNX_Chem_14_06_buffer.jpg)